Intro

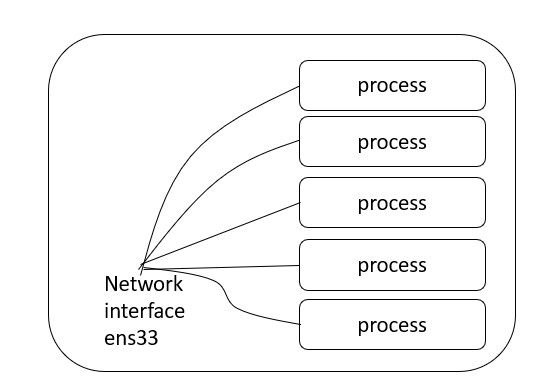

I was recently challenged with the single task of being able to monitor all connectivity in and out of a process. At first thought this is actually fairly easy. “I’ll just use tcpdump” I thought to myself. That single sentence lead me down a rabbit hole of processes, namespaces and the linux kernel. I thought that I would share my experiences of how to do this.

Why do this at all?

The question of why do this at all comes up in people’s heads. Let’s say that I’m a developer and I create a binary that uses some open source libraries for certain functionality. Given that I have imported some open source libraries, I want to categorically understand what the network traffic flow in and out is for my newly minted binary.

This is particularly relevant if I want to let the userbase of my newly minted binary know what firewall ports they need to open up as part of their network connectivity to use my awesome new binary.

Typical development flow

As part of my typical development flow I will create my new application binary. This may or may not be packaged as part of a container.

During the development phase it is highly likely that my awesome new application will operate as a single binary on my developer laptop.

This means that under normal circumstances, that I would have a binary running on my laptop as part of my testing of my new application.

Tell me everything your code connects to

The words tell me everything that your code connects to strike fear in my heart. I don’t necessarily know the answer to that question. This is particularly the case if I am using open source libraries that provide me methods and functionality that I like, but I haven’t yet delved into the detail.

tcpdump to the rescue

At this point most people would say “use tcpdump”. The problem with this approach is that tcpdump doesn’t have the ability to filter on a PID or process id. This means that if I try to trace all of the network connectivity from my application out to the big bad internet that I have to use what I would term a blunt instrument. That is - I capture ALL connectivity between my host and the internet, and I filter based on some assumptions, usually port number or something similar.

This is not an exact answer, and it presents a huge problem to people who (like me) prefer exact answers.

What now?

There are a number of answers here. I investigated a few that turned out to be false starts.

- tcpdump

- strace

- instrumentation

- syscalls

None of them gave me exactly what I needed.

How things work

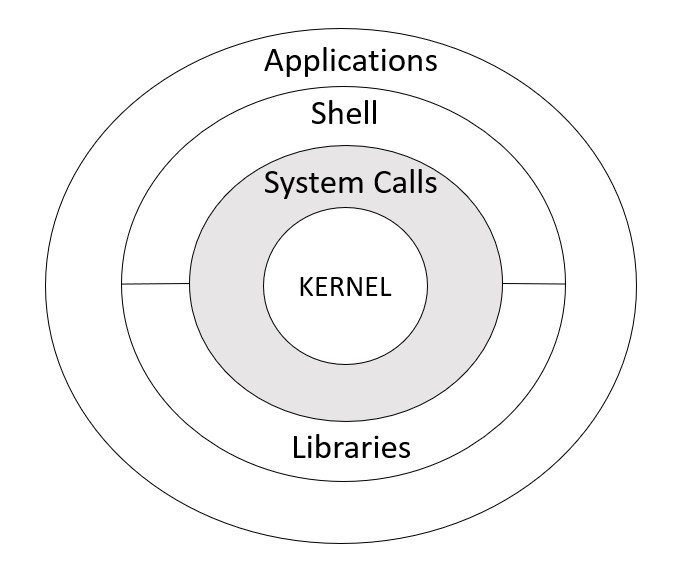

Its important to understand how things work within the linux kernel.

I’ve written before about how understanding the kernel is to understand containers.

This is because the underlying technology that powers containers is embedded in the linux kernel.

Each ring within the linux kernel presents a different level of abstraction and protection within the kernel. Network namespaces operate close to the kernel :)

Network namespaces

One of the pieces of technology that I will be using today is namespaces. I will be using a network namespace to isolate a particular process ID or PID.

Network namespaces virtualize the network stack. A network namespace is logically a copy of the network stack with its own network interfaces, iptables rules, routing tables, sockets and so on.

Tip

Note the following about network namespaces

When created, a network namespace only contains the loopback device. It is then possible to create virtual interfaces or move physical interfaces into the namespace.

A network interface belongs to exactly one network namespace. We will be creating two interfaces. One that exists within the namespace, and one outside of it.

Interacting with a namespace

In order to interact with a namespace, linux has some inbuilt tooling that helps you. I’m using ubuntu in my examples, so all of the operating specific examples that I will be using will be ubuntu based.

If I check the network interfaces that are already a part of my server, I can see the following:

root@ubuntu-test:~# ip -br addr

lo UNKNOWN 127.0.0.1/8 ::1/128

ens33 UP 192.168.50.118/24 fe80::20c:29ff:fe96:7558/64

As can be seen, I have two interfaces. One is a the loopback interface, the other is my interface that is connecged to the ineternet. In my case, I am using a private network to connect out to the internet.

To interact with the namespace, you can use the standard ip command.

In addition to setting IP addresses on interfaces, you can use the ip command to interact with network namespaces in the linux kernel. The snippet below is from the man page for the ip command.

IP(8) Linux IP(8)

NAME

ip - show / manipulate routing, network devices, interfaces and tunnels

IP - COMMAND SYNTAX

OBJECT

netns - manage network namespaces.

Create a network namespace and interfaces

To create a network namespace and interfaces, we can use the following commands.

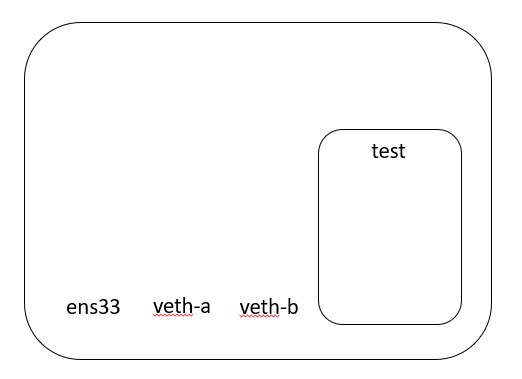

ip netns add test

ip link add veth-a type veth peer name veth-b

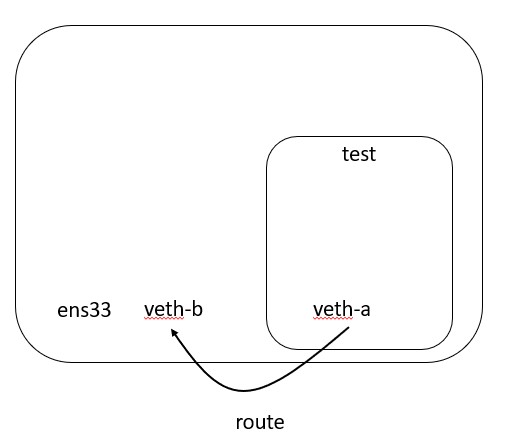

This creates a network namespace that is available. It also creates two interfaces. One interface is created inside the namespace and one interface is created outside the namespace.

After these commands have been run, my interfaces look like this:

root@ubuntu-test:~# ip -br addr

lo UNKNOWN 127.0.0.1/8 ::1/128

ens33 UP 192.168.50.118/24 fe80::20c:29ff:fe96:7558/64

veth-b@veth-a DOWN

veth-a@veth-b DOWN

I have created two virtual ethernet interfaces. Neither ethernet interface is assigned to a namespace yet.

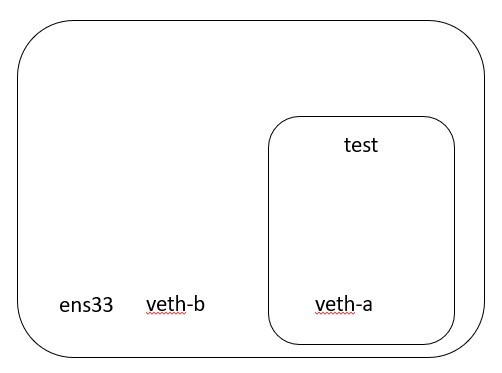

The next set of commands places one of the virtual ethernet interfaces - veth-a - into the network namespace that we just created. The second command configures the virtual ethernet interface with an IP address.

ip link set veth-a netns test

ip netns exec test ifconfig veth-a up 192.168.163.1 netmask 255.255.255.0

Tip

The IP address is configured on the interface INSIDE the namespace

Next we configure the IP address of the virtual ethernet interface OUTSIDE the namespace.

ifconfig veth-b up 192.168.163.254 netmask 255.255.255.0

What do we look like at this point?

At this point we look like the following:

Inside the namespace

root@ubuntu-test:~# ip netns exec test ip -br addr

lo DOWN

veth-a@if4 LOWERLAYERDOWN 192.168.163.1/24

Outside the namespace

Outside out namespace, we have a virtual ethernet interface that has an IP address. This address is on the same subnet as the IP address of the interface that is INSIDE the network namespace.

root@ubuntu-test:~# ip -br addr

lo UNKNOWN 127.0.0.1/8 ::1/128

ens33 UP 192.168.50.118/24 fe80::20c:29ff:fe96:7558/64

veth-b@if5 UP 192.168.163.254/24 fe80::1c6e:3bff:fe62:1555/64

Default gateway

As everything in our namespace looks exactly like a separate entity, we need to provide a default route for everything inside out namespace.

In our case, we are going to provide a gateway that corresponds to the ethernet interface that is OUTSIDE our network namespace.

This will allow us to have connectivity outside of our namespace.

ip netns exec test route add default gw 192.168.163.254 dev veth-a

Routing

Routing becomes a little interesting, but makes sense given the constructs of INSIDE the namespace and OUTSIDE the namespace.

We currently have a default route from INSIDE our namespace that points to an interface that is OUTSIDE our namespace.

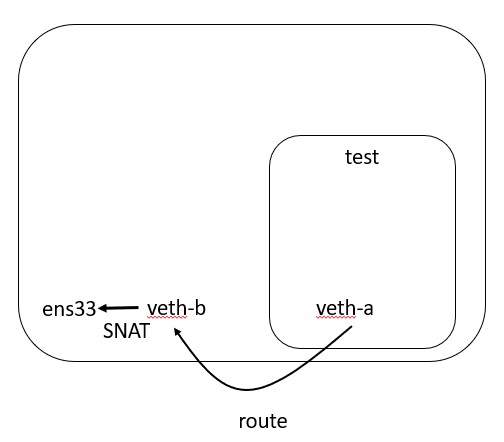

In order for me to route packets to the internet, I need to make sure that I am taking packets that hit my veth-b interface and route them to my real interface that is connected to the internet.

In order to do this, I enable IP forwarding, and create a NAT rule that not only passes packets but also source NATs them to the real internet facing interface.

On ubuntu, I also allow incoming and outgoing connections.

echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -s 192.168.163.0/24 -o <your internet interface, e.g. eth0> -j SNAT --to-source <your ip address>

ufw default allow outgoing

ufw default allow incoming

DNS

Everyone forgets about DNS. In order to make DNS work from within my namespace, I need to configure a resolver using a resolv.conf file. This needs to be done from OUTSIDE the namespace, but reference the fact that the resolver belongs to a network namespace.

Fortunately linux provides a way to do this. Configuration files placed in /etc/netns/ will be used by anything inside the namespace.

mkdir -p /etc/netns/test

echo "nameserver 8.8.8.8" > /etc/netns/test/resolv.conf

Tapping the processes network traffic

If I want to trace traffic in and out of my process, I can simply use tcpdump to monitor the v-ethb interface like this

tcpdump -i veth-b

In order to run a process inside my namespace and see traffic, I would use the following command

ip netns exec test ping 8.8.8.8

This will perform a ping from inside the namespace to a google DNS server. I get the following result from within the namespace

root@testbox:~# ip netns exec test ping 8.8.8.8

PING 8.8.8.8 (8.8.8.8) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=1 ttl=127 time=15.0 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=2 ttl=127 time=13.9 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=3 ttl=127 time=15.6 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=4 ttl=127 time=11.6 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=5 ttl=127 time=13.9 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=6 ttl=127 time=15.9 ms

64 bytes from 8.8.8.8: icmp_seq=7 ttl=127 time=18.5 ms

Tip

I am using the ip netns command to run a process inside the namespace

From outside the namespace, when I use tcpdump to tap the interface that handles traffic solely for the namespace, I see the following

root@testbox:~# tcpdump -i veth-b

tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v or -vv for full protocol decode

listening on veth-b, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 262144 bytes

13:02:05.996794 IP 192.168.163.1 > dns.google: ICMP echo request, id 2651, seq 25, length 64

13:02:06.008609 IP dns.google > 192.168.163.1: ICMP echo reply, id 2651, seq 25, length 64

13:02:06.997659 IP 192.168.163.1 > dns.google: ICMP echo request, id 2651, seq 26, length 64

13:02:07.012764 IP dns.google > 192.168.163.1: ICMP echo reply, id 2651, seq 26, length 64

13:02:07.998639 IP 192.168.163.1 > dns.google: ICMP echo request, id 2651, seq 27, length 64

13:02:08.015410 IP dns.google > 192.168.163.1: ICMP echo reply, id 2651, seq 27, length 64

What does it mean to the developer?

The techniques described above give the developer the ability control their code base, and have complete visibility into how their end product or process is working.

The techniques above can be applied inside pipelines or as part of an automated test framework before deployment.

Conclusion

I terms of a developer workflow, doing all of this might seem overly complicated, but understanding it is essential to being able to understand connectivity of the code that you’re writing. This is particularly the case when you consider that often we use open source libraries in our code base. We may or may not know all of the things that these third party libraries connect to. This is an easy way to find out, by tapping the network connectivity of an individual process.

All in all, this has touched on concepts as diverse as the linux kernel, namespaces and process monitoring. I personally find understanding how these things work to be very useful, and you never know when you need to find the network traffic going in and out of an individual process.