Code first api development

Intro

I recently had a discussion with a friend about what was better with regards to creating API’s. Design First or Code First. The approaches are radically different. We debated back and forth a bit, and I decided what better way to figure this out than to do two four hour sprints and write about the results.

This post is about the first sprint that I did which was the Code First approach.

Design first or Code first

This is the perrenial question when designing APIs. Should I just start writing code and annotate, or should I write an openapi spec and then code?

Design First

This approach is the more traditional API centric approach to creating APIs. This sees the developer write an openapi spec as the first thing that they do. Typically this will use some sort of API tooling like Postman.

This approach focuses on writing tests, and building an API spec first. The code comes later once the specification and tests have been finalised.

Benefits of this approach

The benefits of this approach is that you end up with a design first paradigm and think through your API thoroughly. This approach also lends itself to writing both tests and mocks first, which help speed development signicantly.

Problems with this approach

There are some problems with this approach. The tooling required to take this approach is one. If your tooling only generates an openapi spec for you, then you need to find other tooling that will generate mocks and tests. This is particualrly problematic for me, mainly because my chosen IDE is vi.

There are a plethora of tools available to do this, but you need to try and fail with a few before finding one that works for you.

Code First

This approach is possibly a little mode developer centric in that it sees the developer wirting code first as opposed to an api specification first. Api specs are generated from the code, and from any annotations within the code.

Benefits of this approach

You write tests, you code, then you annotate. This approach is a more natural approach for a developer than writing an api spec first. Start with the tests, then the code, and simply annotate based on your code. This way you’re not writing code to meet your spec, you’re generating your spec from your code.

Problems with this approach

This approach isn’t perfect. You typically end up without mocks. Mocking is a separate part of the process in this approach. This approach also relies on the developer annotating thier code, as well as the tooling being used to generate the documentation being able to cater for different versions of the api spec (v3 and so on).

The API

So I’m using golang today to write a simple git api. This api will respond to a request to clone a repository into a directory, and will accept both the repository name and the branch as inputs into a request to the api.

I’m using some golang components to achieve this. The components I’m using are listed below.

Gin

I’m using the golang library gin-gonic It’s a good framework that has middleware components, validation, route grouping and more.

Go-git

URL: https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/go-git/go-git/v5

I’m also using the golang library go-git for the git components. This is a good library that has great coverage of git. For my purposes I only use clone and pull, but it has good coverage across the spectrum.

Swaggo

URL: https://github.com/swaggo/swag

Lastly, I’m using swaggo to generate the documentation. Again, this is a good framework with great coverage.

The Code

For the purposes of this article I’ve used a single file or monothlithic approach to my api. Normally I would use an MVC or model view controller pattern, with multiple files, and imports, but it’s easier to explain what’s going on when everything is in a single file.

…don’t hate me too much :)

We start with a basic gin api that has a single route. This is a good way to test my api to make sure that the components work before moving on to a functional implementation.

package main

import (

"net/http"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

func homeLink(c *gin.Context) {

// send to swagger docs

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, gin.H{"data": "Welcome Home!"})

}

func main() {

router := gin.Default()

router.GET("/", homeLink)

router.Run(":8080")

}

We can test it out like this:

# go run main.go

[GIN-debug] [WARNING] Creating an Engine instance with the Logger and Recovery middleware already attached.

[GIN-debug] [WARNING] Running in "debug" mode. Switch to "release" mode in production.

- using env: export GIN_MODE=release

- using code: gin.SetMode(gin.ReleaseMode)

[GIN-debug] GET / --> main.homeLink (3 handlers)

[GIN-debug] [WARNING] You trusted all proxies, this is NOT safe. We recommend you to set a value.

Please check https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/gin-gonic/gin#readme-don-t-trust-all-proxies for details.

[GIN-debug] Listening and serving HTTP on :8080

[GIN] 2022/07/10 - 22:22:31 | 200 | 111.898µs | 10.1.1.150 | GET "/"

When I check from a client I see the following:

[root@fedora ~]# curl http://127.0.0.1:8080

{"data":"Welcome Home!"}

PERFECT!!!

Functional Implementation

At this point, I’ve got a basic api that works. Let me do a quick functional implementation of my git api.

First I add some new routes to my router. I add a /pull route and a /app route.

In my implementation, the pull route does all the work, and the app route is just a stub. Note that the pull route is a POST and the app route is a GET.

func main() {

router := gin.Default()

router.GET("/", homeLink)

router.POST("/pull", gitPull)

router.GET("/app", newApp)

router.Run(":8080")

}

Next I create two new handlers functions for my api. One for the pull and one for the app. Each function corresponds to a route.

Pull function

This function does the real work. The interesting pieces of the function here are that the gin server performs validation on the JSON that is passed into the api as part of a POST request.

json := struct {

// We don't need a destination here as we will be using a standardised destination on the server

Url string `json:"url" binding:"required"`

Branch string `json:"branch" binding:"required"`

}{}

if err := c.BindJSON(&json); err == nil {

The struct defines the amount POST data that comes to the service. This says that we have two parameters that we accept, Url and Branch. Each of these is passed in as a string.

The code below attempts to bind the inoming data portion of the request to the struct above.

if err := c.BindJSON(&json); err == nil {

// IF NO ERROR IN BINDING

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, gin.H{

"url": json.Url,

"branch": json.Branch,

})

The functional part of my API takes the data portion of my JSON and then does either a git pull or a git clone depending on whether or not the repository already exists. Using the go-git API I clone the REF that’s the current branch I want. Then if I have an error that says the repository already exists, I move to doing a pull rather than a clone.

// Perform GIT pull as a first try

targetUrl, err := url.Parse(json.Url)

r, err := git.PlainClone("/apps/" + path.Base(targetUrl.Path), false, &git.CloneOptions{

URL: json.Url,

ReferenceName: plumbing.ReferenceName(fmt.Sprintf("refs/heads/%s", json.Branch)),

SingleBranch: true,

Progress: os.Stdout,

})

fmt.Printf("goober: %s\n", r)

if err != nil {

//At this point, if there is something in the repository it means it has been cloned before

//We should do a pull to update it rather than a clone.

if err.Error() == "repository already exists" {

r, err := git.PlainOpen("/apps/" + path.Base(targetUrl.Path))

w, err := r.Worktree()

pull := w.Pull(&git.PullOptions{

RemoteName: "origin",

ReferenceName: plumbing.ReferenceName(fmt.Sprintf("refs/heads/%s", json.Branch)),

})

fmt.Printf("repo exists path: %s\n", r)

fmt.Printf("repo worktree: %s\n", w)

fmt.Printf("pulled error: %s\n", err)

fmt.Printf("pull: %s\n", pull)

if err != nil { fmt.Printf(err.Error()) }

} // end if repository exists

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, gin.H{

"error": err.Error(),

"message": json.Url})

return

} // end if error on Plainclone

} else {

fmt.Printf("stuff: %s\n", json.Url)

// IF WE HIT HERE IT MEANS THERE IS AN ERROR IN BINDING

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{

"error": "VALIDATEERR-1",

"message": err.Error(),

})

} // end if/else bindJSON

}

App function

In this example, the app function doesn’t do anything, it’s just a functional stub.

func newApp(c *gin.Context) {

// Send new request to local unit that configures an app

// need language type as a varible.

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, gin.H{"data": "NEW APP"})

}

Annotations

Annotations on my API are very easy using swaggo. Annotations are added after importing the swaggo library. Annotations are added directly to my code, and are not separate.

There are different annotations for the router versus the individual functions or routes.

Router Annotations

Router annotations are general in nature and represent the “main” notes that you will see as part of your API. These are attached to the router component. In this case I’m using gin. You will note the last route that defines my swagger page.

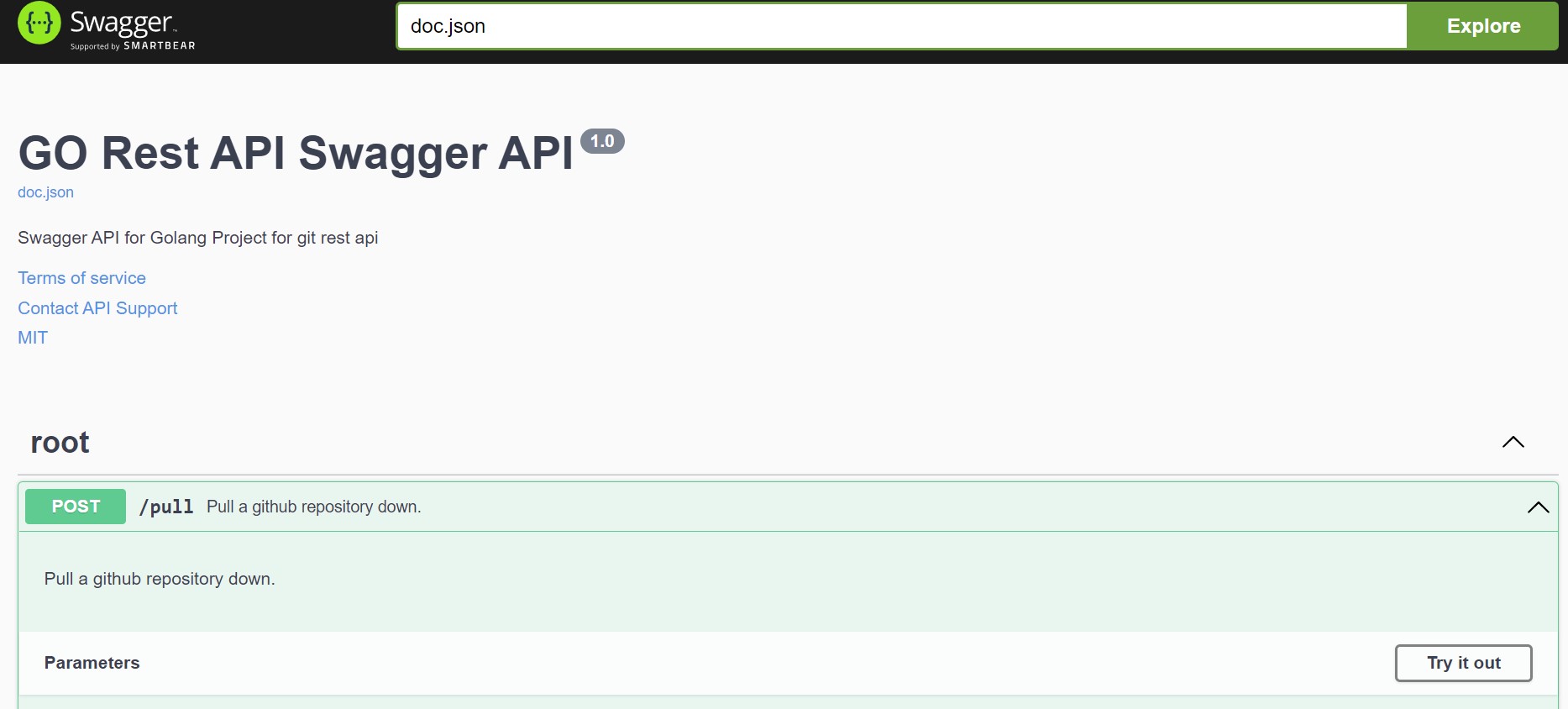

// @title GO Rest API Swagger API

// @version 1.0

// @description Swagger API for Golang Project for git rest api

// @termsOfService http://swagger.io/terms/

// @contact.name API Support

// @contact.email svk@codecowboydotio

// @license.name MIT

// @license.url https://github.com/codecowboydotio/go-rest-api/blob/main/LICENSE

func main() {

router := gin.New()

router.GET("/", homeLink)

router.POST("/pull", gitPull)

router.GET("/app", newApp)

router.GET("/swagger/*any", ginSwagger.WrapHandler(swaggerFiles.Handler))

router.Run(":8080")

}

I have a corresponding handler that points / back to my docs - it’s a neatness thing.

func homeLink(c *gin.Context) {

// send to swagger docs

c.Redirect(http.StatusFound, "/swagger/index.html")

}

Function Annotations

When I come to my function, there are a different set of annotations that I can use to generate my docs. Each of the annotations is applied, and I can set parameters, success and failure as part of the documentation.

Where I define the success criteria, I can pass in a model and this model will be used to automatically fill out my swagger docs.

// @BasePath /api/v1

// HealthCheck godoc

// @Summary Pull a github repository down.

// @Description Pull a github repository down.

// @Tags root

// @Accept application/json

// @Produce json

// @Param branch body string true "Branch Name"

// @Success 200 {object} map[string]interface{}

// @Router /pull [post]

func gitPull(c *gin.Context) {

Generation

I do need to run an external program that generates the docs for me. As part of the installation of the swaggo library and packages, I get a binary installed in my GOPATH directory. In my case, because I am breaking a lot of rules in my dev environment, this is in /root/go/bin.

yes I know running everything as root on my dev box is bad

[root@fedora go-rest-api]# /root/go/bin/swag init

2022/07/18 21:03:07 Generate swagger docs....

2022/07/18 21:03:07 Generate general API Info, search dir:./

2022/07/18 21:03:12 create docs.go at docs/docs.go

2022/07/18 21:03:12 create swagger.json at docs/swagger.json

2022/07/18 21:03:12 create swagger.yaml at docs/swagger.yaml

Running the swag init command uses the defaults and generates my swagger docs from my annotations.

What’s it look like?

So what does this look like once I’m done?

After generating the docs, I have a docs directory that holds my swagger docs. I end up with three files below.

[root@fedora docs]# ll

total 12

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2329 Jul 18 21:03 docs.go

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1646 Jul 18 21:03 swagger.json

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 860 Jul 18 21:03 swagger.yaml

- docs.go: This is a golang package representation of my swagger document.

- swagger.json: This is a standard swagger or openAPI definition.

- swagger.yaml: This is a standard yaml representation of my swagger or openAPI definition.

Typical development flow

This is something of a typical development flow. It looks messy, but it captures a lot of what we do when we develop APIs from a developer perspective.

We write tests, create mock servers, write code, perform functional tests, then go back and write more code, perhaps write some more mock servers and tests, refactor, and eventually we release something.

The point is that it’s a non linear process.

Conclusion

There are two things that I set out to achieve here:

- Learning how to annotate code in golang as a way of generating swagger / openAPI docs.

- Testing how good / efficient / valid code first is as a technique.

What I learned with code first

There are a few things I learned using the code first technique.

The good

There are a lot of good things about a code first technique.

- It is fast.

- It has a laser focus on a functional implementation.

- It is super agile.

The bad

- It is laborious to continually annotate.

- It does not lend itself to a good developer experience with the end product.

The ugly

- I never wrote mocks.

- I barely wrote tests.

- Deep down I know this will be less maintainable / controllable by other people.

When to use it

I think that if you’re writing a super fast MVP, or doing a short sprint where you’re trying to show functionality above all else, then it’s an appropriate technique and annotations in the code are equally as fast.

If you do a proper MVC implementation (which I did not) then the annotations will be even easier to implement.

If developer experience in your end product matters a lot, then you should probably look at API first :)